What Makes Earth (Geologically) Habitable?

A broad question, sure enough, and one that I cannot do justice here. Given that the sample size of observable habitable planets is precisely 1, we are extraordinarily limited in our judgement of life-essentially planetary processes. Generally, the presence of plate tectonics on Earth gives rise to a planet-wide carbon and water cycle (that is, the subduction-based tectonic regime we find here on Earth). The partial melting involved in plate tectonics also generates high-standing continental crust which can sequester carbon through weathering. Therefore, plate tectonics are though to be the dominant climate regulator for terrestrial planets.

Plate tectonics on Earth can be boiled down to this: hot oceanic crust forms at ocean ridges, and then sinks back into the mantle after a period of cooling and increasing density relative to the underlying mantle. These “plates” contain water, carbon, and sediments from their time at the surface, therefore providing a surface-to-interior cycling mechanism that regulates climate and interior composition. In the broadest sense, this process can separate the habitability of Earth from Venus.

How Do We Link This Process to Exoplanets?

A “rocky” terrestrial planet (as opposed to gaseous planets like Jupiter) generally reflects the bulk refractory (i.e. high condensation temperature elements) composition of its host star. This is of no surprise, as a star and its planets mainly form from the same nebular cloud of material.

In a vastly simplified modeling environment, we assume that the Earth is only made of refractory elements (for the rocky parts of the planet and neglecting oxygen, this is a very acceptable simplifying assumption). By assuming that the entire Earth initially exists in a melted state, we apply the MELTS algorithm (Ghiorso et al. 1995) to solidify the planet under Earth-like pressures, temperatures, and oxygen fugacity. We are then able to recover the compositions of the Earth’s core, silicate mantle, and basaltic crust to an accurate degree. By applying this same Earth-based model to the compositions of other stars measured via spectroscopy, we can simulate the formation of an Earth-like planet around other stars. By modeling density-versus-depth contrast of the planet’s lithosphere versus its silicate mantle, we can quantify the likelihood for Earth-like, subduction-based plate tectonics.

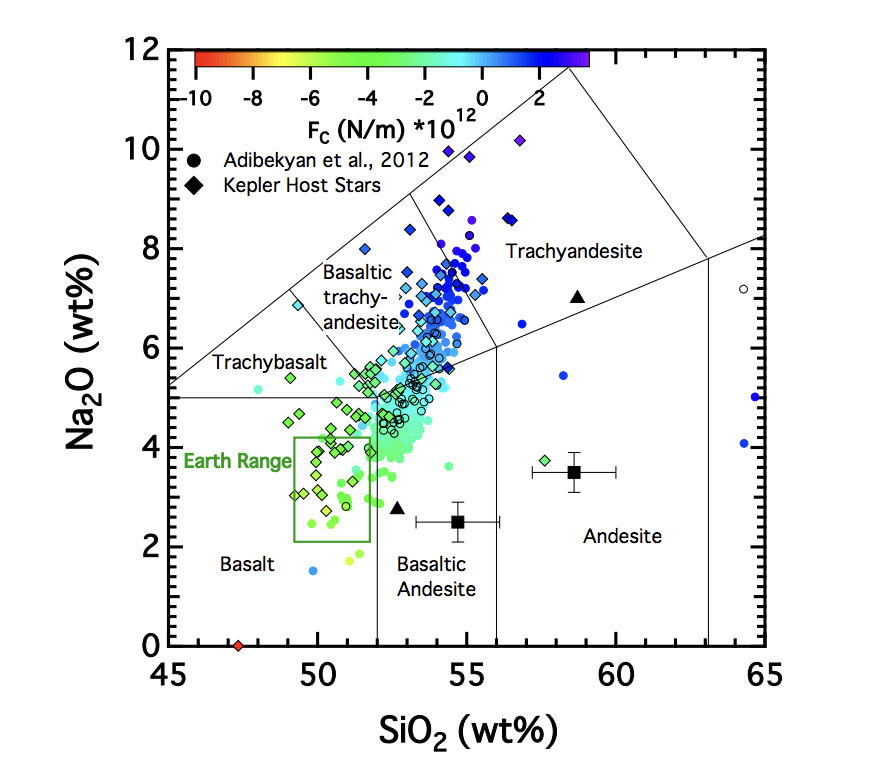

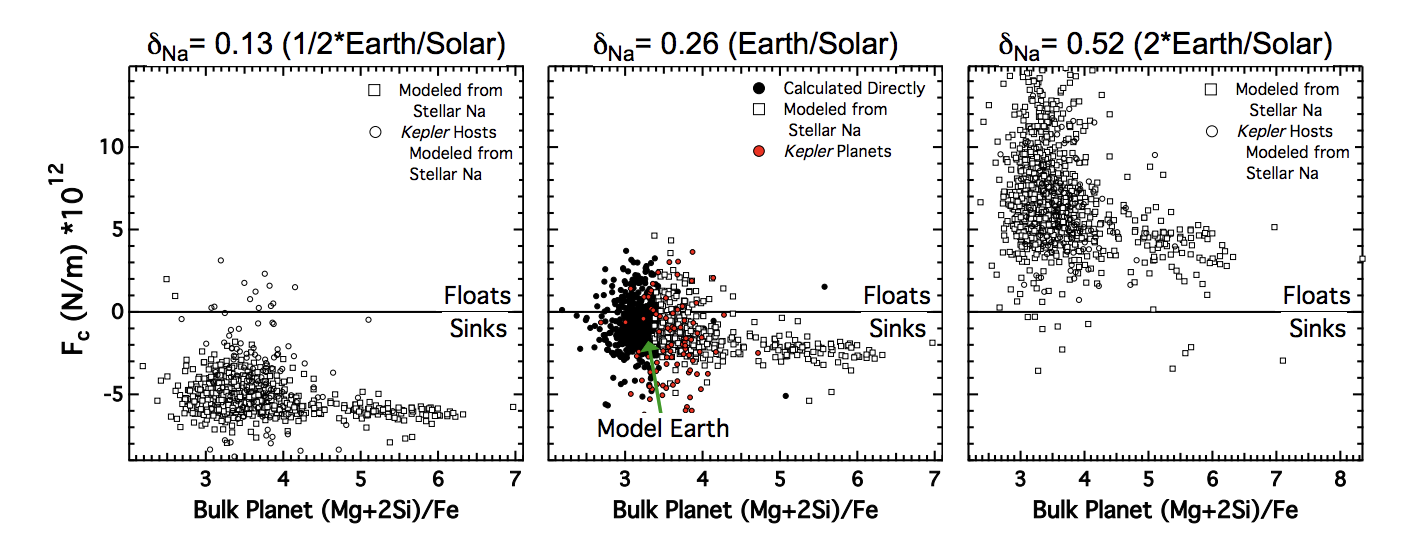

The figure above represents simulated exoplanetary mid-ocean ridge basalts from ~1200 stellar samples from the Adibekyan et al. 2012 stellar survey. One remarkable result of the study is that sodium, a moderately volatile and incompatible element (that is, concentrated in the crust), provides significant upward buoyancy to planetary lithospheres. However, due to its more volatile nature, it is not a good reflection of the star-to-planet compositional relationship. Therefore, studies related to sodium volatility in new planets should be considered in the future. Below, the impact of doubling or halving sodium abundances in the planets can either make most of the modeled lithospheres float or sink, respectively.

For more information, please see our pre-print paper on this study here.